Recently I saw a TikTok (I’ve deleted the app now, okay? Don’t look at me like that) of images a starry-eyed Gen Z had collated of high school style in the 2000s. The comments on the video were all fellow young whippersnappers commenting things to the effect of how “back then” (ugh) looked like a cooler, better, friendlier, more inclusive time; apparently, the 2000s were a smartphone-free utopia of mindfulness and neighbourly love.

Um. Okay. As someone who hit puberty in the early 00s, I remember things a little differently.

Ah, the noughties. A decade that saw global recession, the word “terrorism” become part of our everyday lexicon, and the Internet finding its way into our homes. A decade where many discriminatory and problematic things were considered a-ok that would decidedly not fly in the 2020’s.

Also the decade in which I, and many others, battled poor body image and even eating disorders, no doubt helped along by the trend of ultra-slenderness in 2000s media and the prevalent cultural fixation on extreme thinness at the time. I know I’ve seen other millennials speak out about the impact of the media we grew up with on their body image and that I’m not alone in how a cultural obsession with thinness managed to seep into my ordinary little life.

Now, I’m not saying other decades were, or are, a golden utopia of body positivity, but you have to admit that the decade between 2000–2010 had its own very distinct flavour of toxic body image. I mean, the phrase “heroin chic” was a tongue-in-cheek term used to describe one of the trendiest looks of the mid-90s to early 2000s: gaunt thinness akin to that of a hardcore drug user.

Sites like The Skinny Website existed, where candid paparazzi pictures of celebrities were posted for open-slather mocking of their weight and every barely-perceptible flaw. I remember Evangeline Lilly, Kristen Stewart, Leighton Meester and Mischa Barton being among the actresses regularly ridiculed for their mere mortal figures. I also remember these photographs of Kim Kardashian eliciting an absolute bloodbath in the comment section about how fat and disgusting she was, to dare to have human flesh and eat ice-cream in broad daylight like that.

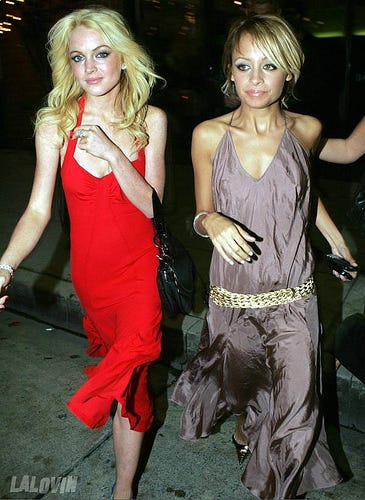

Conversely, in the media, many celebrities at the time were visibly underweight. (I can’t imagine why they might have felt the need to lose weight. Can you?)

Off the top of my head I can recall the extreme thinness of Hilary Duff, Lindsay Lohan, Mary-Kate Olsen, Nicole Richie and Ashlee Simpson, all young women in the public eye in the 2000s who likely felt the pressure to be thin, and all of whom I recall being both scrutinized for both their pre- and post-weight loss bodies. I distinctly remember one magazine I bought when I was in my early teens with photos of skinny hollywood stars and the heading “STARVE WARS” splashed across the front cover with seemingly no awareness for why these young actresses were fading away before our eyes.

I mean, you could say it was a touch toxic out there.

I remember being 10 or 11, standing in a video rental shop with my parents and my Dad frowning up at a poster for Bridget Jones’s Diary. I heard him say to my Mum, “I don’t know why everyone is talking about how much weight she gained, she doesn’t look that bad.”

Now I was staring up at that poster, too, and I was surprised. To little me, Renée Zellweger looked just like all the other pretty, white, blonde women in movie posters. People considered this fat? It blew my childish mind. How could I be so deluded not to see what everyone else around me apparently could?

Apparently, whatever line there was that divided “beautiful” and “disgusting”, this Bridget Jones lady had well and truly crossed it. I made a mental note: People don’t like that, so don’t look like that.

A few years later, at the age of 14, I worked out how to convert my weight from kilograms into pounds and was absolutely devastated to realise that I weighed the same as Bridget Jones did in the film. I distinctly remember thinking, “I’m as fat as Bridget Jones, and she was a grown up.” I was mortified.

There were so many weird, nonsensical, toxic fixations on women’s bodies in the media I was exposed to as an adolescent. Remember the episode of Friends where the boys suggest that one of Rachel’s flaws is her ankles being “a little chubby”? Or in How I Met Your Mother, that Ted Mosby seems to fear dying alone to an almost pathological degree, but never once considers dating a woman over a US size 6? (In one episode, he even rejects a woman who used to be overweight because he so deeply fears she will get fat again.)

I know that I will never forget the episode of Scrubs where a pregnant Jordan described her thighs overlapping the sides of the toilet when she sat down as a sign of being unacceptably enormous. Putting aside how bothered I was by the unrealistic skinny glutton aspect of Liz’s Lemon’s character in 30 Rock, I always felt a bit defeated about how slender Liz was treated as ‘fat’. The episode where Liz asks Jack if he’s going to guess her weight and Jack replies, “You don’t want me to do that,” implying that Liz wasn’t thin enough, and then later announcing that Liz weighs a whopping 127lbs/57.6kg especially bothered me. Were we supposed to pretend that 57 kilograms was enormous, or something?

Then there were the films. For the most part the female leads in films are very slender and that’s treated as the standard in Hollywood, but I’d never seen it put forth so blatantly as it was in 500 Days of Summer when the titular Summer is described as being of “average height” at 5’5’’, and of “average weight” at 121 lbs/55 kg. I was so thrown by this description; wasn’t 121lbs considered skinny? Now I was hearing it was just plain ol’ “average” as in “normal” or “meh, you could probably aim higher.”

For The Devil Wears Prada, Anne Hathaway was told to gain ten pounds (roughly 4.5kgs) to play aspiring writer Andy Sachs, and then promptly made to lose it again when none of the on-set wardrobe fit her. I don’t know what’s worse; that in 2006 Hollywood, 10 pounds was the difference between the A-list hotness of Anne Hathaway and “the smart, fat girl” she played in the film, or that we all had to watch this movie and pretend that skinny Anne Hathaway in a bulky blue jumper was believably chubby enough to be on the receiving end of countless fat jokes.

A similar thing occurred in the the Sex and The City movie when Samantha “gains weight”. When Charlotte, Carrie and Miranda first see Samantha’s “gut” they react as horrified as if she’s casually turned up to a christening with a raging case of smallpox. At one point Carrie even asks her, “How- and I say this with love- how could you not notice?” In reality, Kim Cattrall didn’t even gain any weight for the scene; the film’s stylist just dressed her in slightly tight clothing to give the illusion of weight gain. Once again, the audience dutifully pretends that an above-average looking woman with a below-average BMI is anything but.

Is it any wonder a few of us were warped by this odd and illogical representation of weight in the media we were exposed to? I, for one, am not surprised that some of us meandered through the 2000s obsessed with our waistlines, jittery on caffeine and with an encyclopedic knowledge of calorie counts.

I can’t help but think that things have changed for the better.

The fact that Gen Z might look back on decades past as a nicer, kinder time doesn’t actually bother me. I get it; as time marches on and memories soften, the past becomes imbued with a sepia-hue and is perhaps recalled more fondly. When you view a time through vague memories and photos of happy, document-worthy moments, or the films, shows, and music worth remembering, you might begin to romanticise decades past.

It’s human nature, really.

However, I think it’s important to realise that the 2000s were not a perfect, pre-Internet decade of friendliness and contentment. It’s important to remember how far we’ve come and to recognise the cultural shift towards body positivity over the last decade or so.

While today we now have a whole new crop of beauty standards that didn’t exist in the noughties, we also have a much more diverse representation of bodies in media. Let’s not underestimate the value of young women to see bodies like their own represented in the media they consume, to feel a sense of acceptance and belonging. Sure, thinness is still the norm in television and movies, but seeing women like Iskra Lawrence celebrated for their figure, or Barbie Ferreira cast in Euphoria, or Lizzo gracing the cover of Vogue should serve as a reminder that we’re making headway, even if it is slow and reluctant.

In 2021, our approach to body positivity in media is far from perfect, but I’d like to think we’ve come some way since the days of Bridget Jones’s Diary.